|

What an incredible day! It was a bright, crisp, and slightly windy fall New England day that unfolded into a vibrant celebration of community, family, and love. We want to express our heartfelt thanks to everyone who stopped by to say hello and learn about the indigenous tribes of the Philippines, particularly the T'Boli.

Harvard Square was alive with enthusiasm, pride, and the unique rhythms, dances, crafts, and cuisine of the Philippines. We had the pleasure of meeting many wonderful people within the local Boston Fil-Am community. One woman approached us at the MgaKwento booth, her face filled with wonder, and said, "I've lived here for 22 years, and I've never seen so many Filipinos in Boston." Her smile spoke volumes—she felt a sense of belonging and a taste of "home." We'd like to extend our gratitude to everyone who supported local artists Lewanda and Zoe. Zoe made her debut with her handmade ceramic pendants inscribed with Baybayin script. Thank you for being a part of this beautiful day!

0 Comments

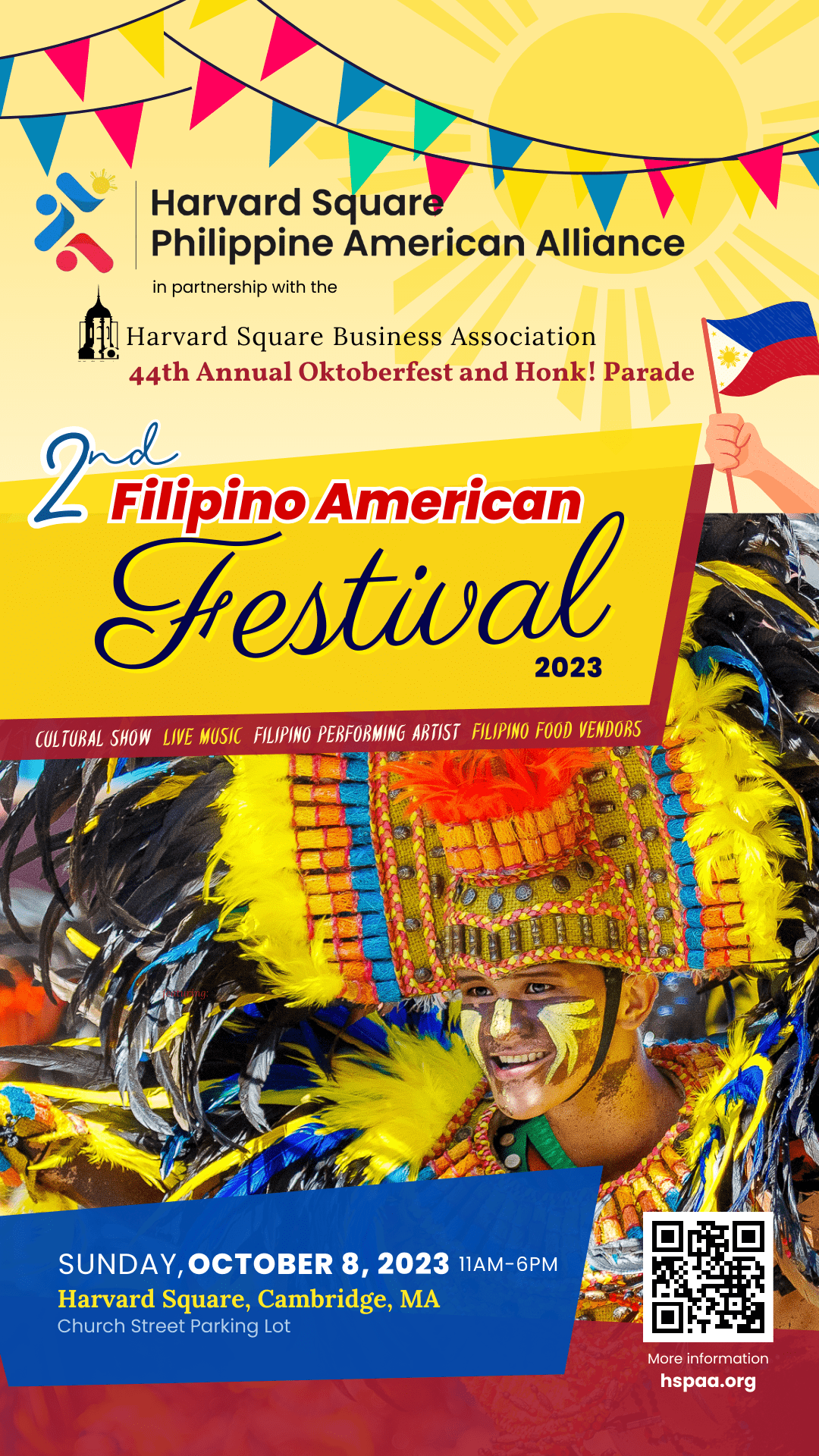

Tindahan "store"MgaKwento Pop Up Store will be featured on October 8, 2023 in Harvard Square, Cambridge, MA! Join us at the 2nd Philippine American Festival from 11 AM- 6 PM on Church St, Harvard Square. Lewanda will be selling original T'Boli weavings called, T'nalak. In early 2023, Lewanda visited the T'boli tribe in South Cotabato, Philippines and met the weavers that make this beautifully handcrafted fabric. MgaKwento will be selling decor, wall hangings, hand-beaded tribal jewelry, baybayin jewelry, artwork and more.

In March 2023, Lewanda went back home to visit her ancestral and family land in Mindanao. She hopped on a local "habal-habal" and ventured out to visit the T'boli people and meet the dream weavers that make the handcrafted T'nalak cloth.  T'nalak weaving is part of the intangible cultural heritage of the Tboli people,[1] an indigenous people group in the Philippines whose ancestral domain is in the province of South Cotabato, on the island of Mindanao in the Philippines. T'nalak cloth is woven exclusively by women who have received the designs for the weave in their dreams, which they believe are a gift from Fu Dalu, the T'boli Goddess of abacá. Lewanda's latest painting "1904 World's Fair"

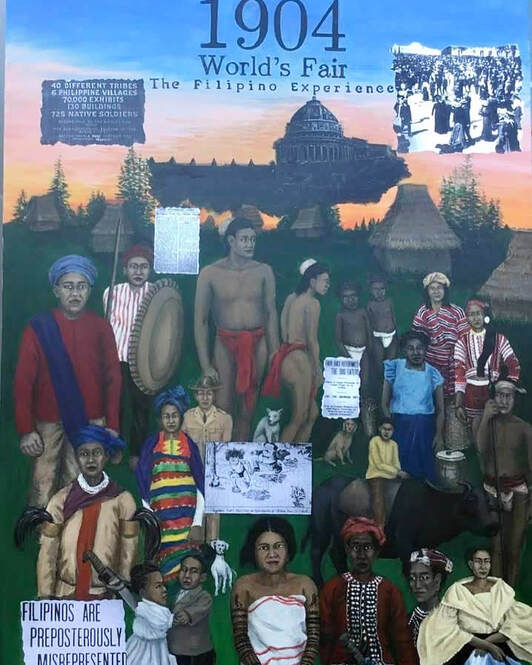

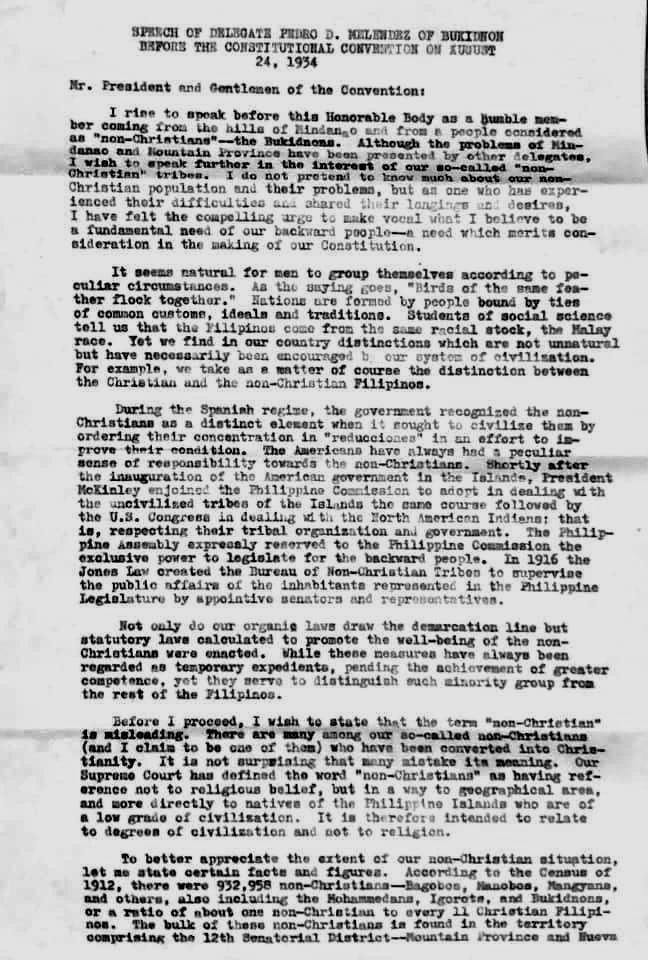

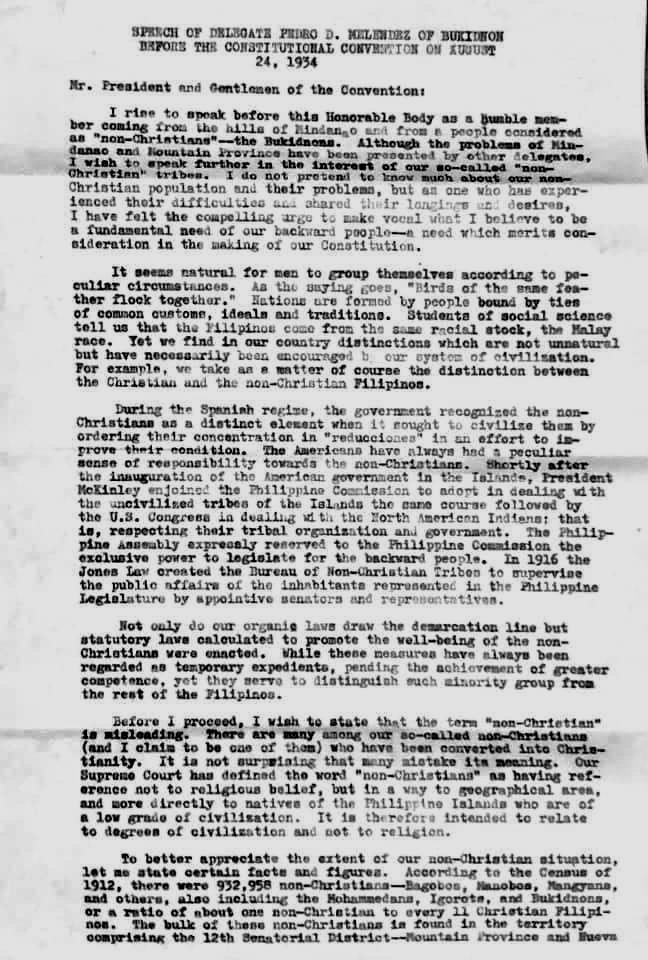

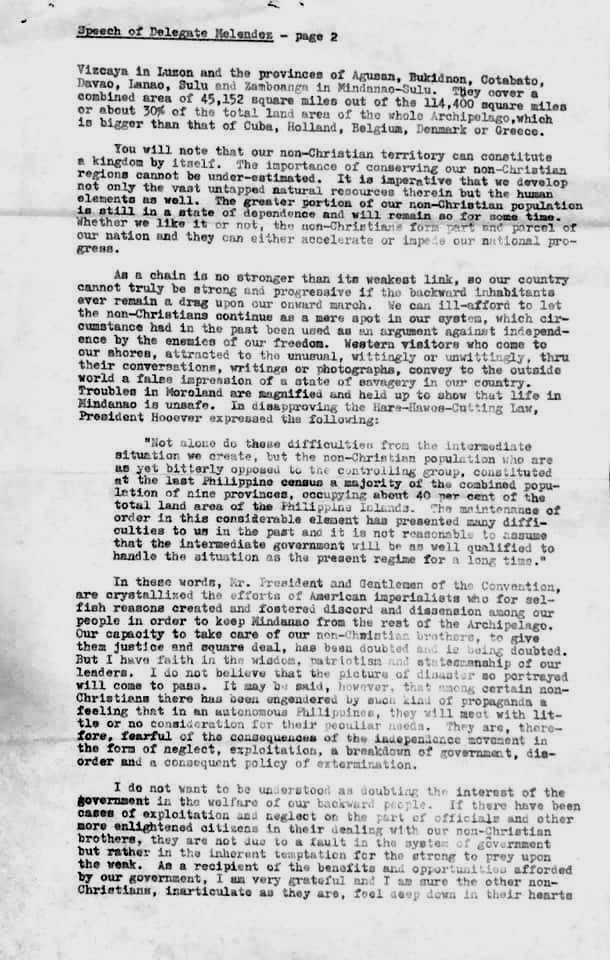

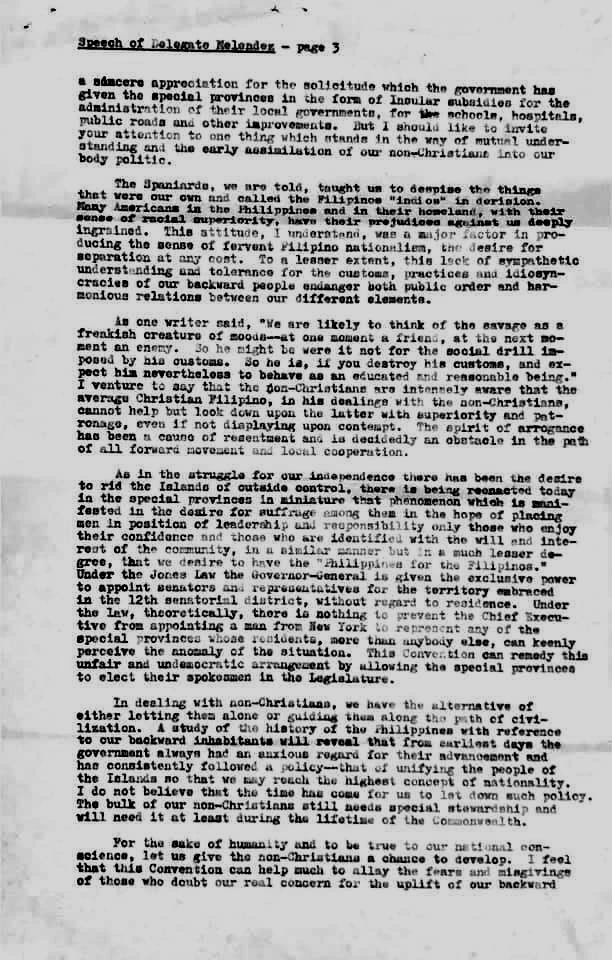

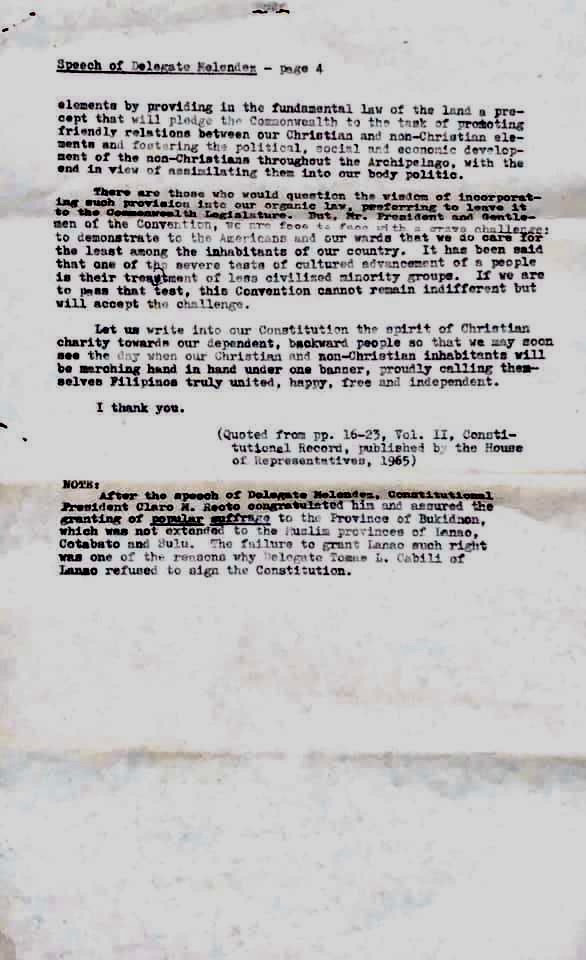

1904 World's Fair. 2021. Acrylic. 36” x 48” Just a few years after the Philippines was annexed by Spain to the US, it was represented in the 1904 World Fair in St. Louis, Missouri. In an extraordinary and sprawling manner, the fair was a venue to showcase an American achievement and entry into the world stage as an imperial power. The ethnic tribal character of the newly acquired colony was prominently displayed in simulated settings. Certain tribal practices were featured and attracted huge audiences because of the sensational ways they were shown. Over-all, the idea was to represent the Philippines as a backward and less civilized country that needed to be educated and modernized by a benevolent colonizer. This lop-sided presentation of the Philippines angered some people but their protests were drowned out by the prevailing big brother sentiment of the public and government. On August 24, 1934 my Lolo, delegate Pedro D. Melendez addressed the Constitutional Convention. Here is his original speech. He was an advocate for the native peoples and tribes of his region, Bukidnon. He notes the North American's subjection of its' indigenous people and parallels that atrocity as insight to the importance in preserving the "non-Christian" Filipinos and other vibrant tribal communities. "You will note that our non-Christian territory can constitute a kingdom by itself. The importance of conserving our non-Christian regions cannot be under-estimated." #familyhistory #filipino

I'm currently attending my first PoCC (People of Color Conference) hosted by NAIS and my eyes have been filled with tears. The conference's title, "New Decade, New Destinies- Challenging Self- Changing Systems- Choosing Justice" hold the surface of this magically elevating experiences as a POC in a PWI. It's been my first experience sharing space in a micro-affinity group with other 1st generation Filipinx professionals. Wow. So many beautiful brown faces illuminated my screen. Attending this conference virtually because of the global pandemic has some advantages. One is the accessibility it creates for it's attendees- there are over 2,000 BIPOC professionals in attendance. In the AAIP Affinity space there were over 250 members in "room". In the micro-affinity space Filipinx identifying folx held 8 break out rooms (80?). Second, I get to see all the faces on my screen- a mosaic of humans from all parts of the US and internationally.

A pivotal session during this conference titled, "Island Womxn Rise, Walang Makakatigil: Collectivist Cultural Approach For Healing, Sustaining, and Inspiring" discussed the meaning of "Kapwa" . According to Professor Virgilio Enriquez, founder of Sikolohiyang Pilipino. “Kapwa is a recognition of a shared identity, an inner self, shared with others. This Filipino linguistic unity of the self and the other is unique and unlike in most modern languages. Why? Because implied in such inclusiveness is the moral obligation to treat one another as equal fellow human beings. If we can do this – even starting in our own family or our circle of friends – we are on the way to practice peace. We are Kapwa People.” This term, "We are Kapwa People" will reside within me now. I'm truly grateful to have found this space of unity, acceptance and belonging.  I'm New Here: Perspectives on Migration juried by Boriana Kantcheva October 27, 2018 - January 18, 2019 Opening Reception, October 27th at 7 PM Arlington Center for the Arts 20 Academy Street, Arlington, MA 02474 This exhibit will feature prominently in the grand re-opening celebration of the new Arlington Center for the Arts this fall. After three years of challenge and change, ACA is on the cusp of moving into our new home. Reflecting on this major organizational transition, and with an eye on larger themes of migration in our broader world, we invite you, our artist community, to help mark this transition with an exhibit of artwork reflecting on themes of migration, change, transformation, and the meaning of home. I’m New Here seeks to inspire dialogue and learning about issues of migration and immigration as they apply in our community and in the world at large. This exhibit will show artwork addressing the themes and experiences of human migration, voluntary or not, for social, political, and economic reasons, and the experiences of resettlement. Themes include: asylum and assimilation, borders and boundaries, citizenship and crossings, identity/identities, and the meaning of home. One on Lewanda's pieces from her series "Telling Our Story" will be featured, "Lolo, Please Go Sledding with Me" (2000, Acrylic on Canvas, 30"x36") Working Conditions Opening Reception

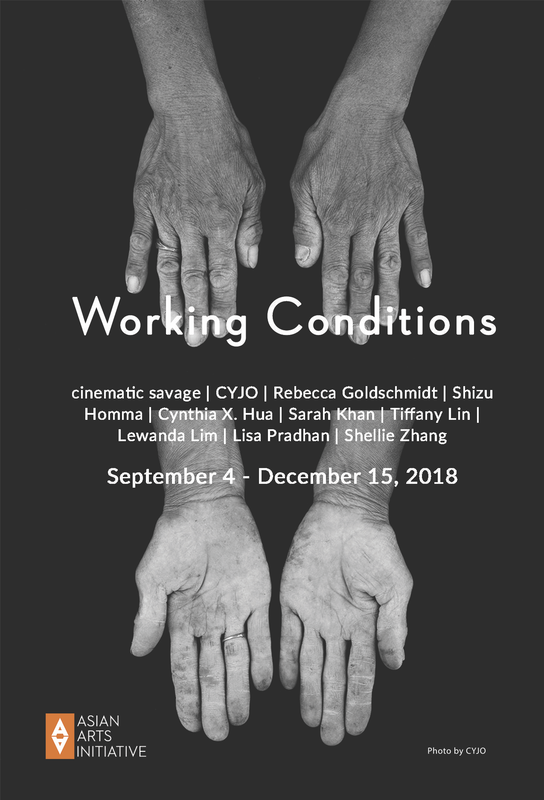

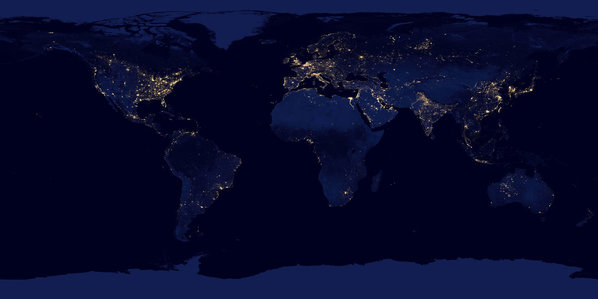

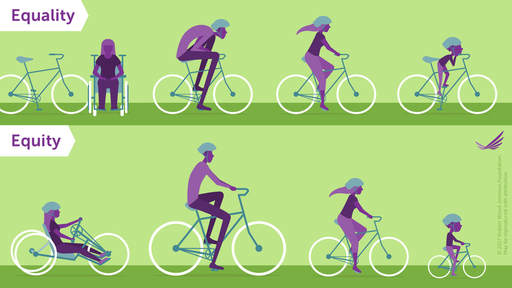

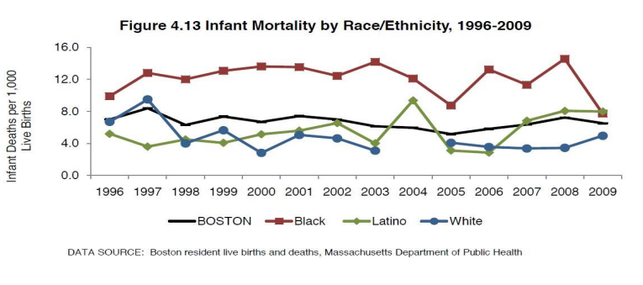

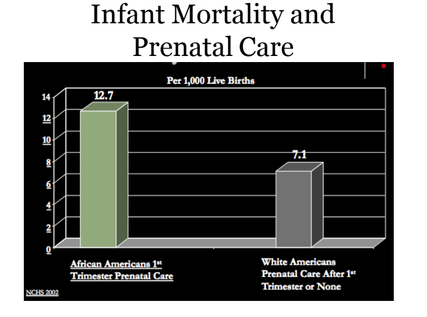

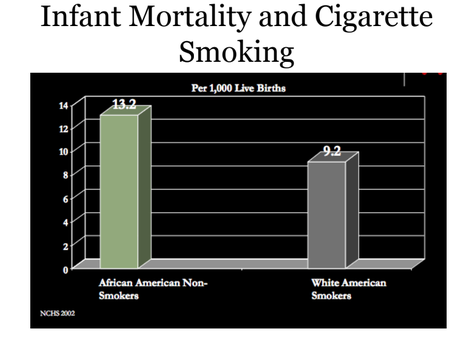

Friday, September 7, 6 – 8 p.m. Asian Arts Initiative 1219 VIne Street Philadelphia, PA 19107 215.557.0455 Featuring: cinematic savage | CYJO | Rebecca Goldschmidt | Shizu Homma | Cynthia X. Hua | Sarah Khan | Tiffany Lin | Lewanda Lim | Lisa Pradhan | Shellie Zhang Exhibition runs September 4 – December 15, 2018 Asian American lives are shaped by the concept of labor, whether working in factories overseas, as caretakers in the United States, or performing the emotional labor of smiling every time someone asks “Where are you from?”. The artists in Working Conditions utilize a variety of strategies—performance, video, painting, installation, sculpture, and mixed media—to illuminate the ways in which labor operates on a global and a personal level. The opening reception will feature: Performance by Rebecca Maria Goldschmidt In the Filipino kitchen, vinegar is an omnipresent ingredient, but beyond its culinary value, it also serves as a medicinal and spiritual tool that has been essential to our survival. Nabanglo a lamisaan is an interactive installation inviting audiences to experience sukang ilocos, a sugarcane vinegar, and recall their own memories of bitterness, perseverance, and labor, as they learn about key historical events. Performance by Shizu Homma Reflecting on her personal labor history, Shizu Homma will perform traditional Japanese embroidery at the opening reception and additional performances during gallery hours and have finished needlework to frame. Visitors are invited to ask her about work she has done—illegal, legal, voluntary, coerced, paid, and unpaid. Homma’s performance will continue during gallery hours from September 10 – September 21. On a chilly New England spring morning (yes, it snows in April here), tucked behind the Southern Jamaica Plain Health Center is a yoga studio where the monthly meeting for the Racial Justice Training Seminar was assembling. The chairs were arranged in a circle, wall mirrors covered by ruby curtains. The skin colors in the room ranged from pinky white to deep dark chocolate, one woman came with her walking assistance device, there were immigrants, descendants of African slaves, a mixed-race woman who wore a bindi on her crown, a southern white woman, gay, queer-identified and one young African American man. It was a kaleidoscope of the American tapestry. It was beautiful. There aren’t many spaces in my current life where I feel the safety of common ground and an unshielded sense of vulnerability. They were strangers yet somewhere I knew they were there because of a full heart to make this world and our community a better place for everyone. I first heard about JPHC’s work around racial justice and racial healing when I heard Abigail Ortiz, MPH, MSW speak at the inaugural Racial Justice Symposium at Boston College in March 2018. She along with Dennie Butler-MacKay presented the collaborative work called “The Racial Reconciliation & Healing Project”. During the symposium and as a ritual introduction, one facilitator pronounced her race, ethnicity and gender pronouns. “I identify racially as a white woman, ethnically as English, Irish and Northern European and use the pronouns she/her/hers”. The other speakers at the symposium introduced themselves in the same fashion. One African American man, comically (but seriously!) identified as “Wakandian” which resonated with the audience in laughter and solidarity. This particular training seminar was catered toward healthcare workers and adults however the core of this program’s important work is for adolescents and young adults. The youth participate in a year long biweekly meetings to foster the increased connection with themselves, their peers and the world. Linked here is the video that the youth made describing the program. The seminar could easily engulf one into a Ph.D. thesis work of in-depth research, analysis, and on-going discussion, unfortunately, we only had two hours to digest all this material. The summary style of this training was thought-provoking and a heavy reality that has stimulated me to continue talking about this topic. The topics that struck me most are summarized below. The introduction began with the framework of “Radical Democracy “. “Radical Democracy political framework focused on structural racism. This framework assumes that racism, “a system of advantage based on race” (David Wellman), operates through policies, practices, systems, and structures that work in tandem with other forms of oppression to maintain a state of white supremacy, patriarchy, and capitalism.” (from racialrec.org website) The facilitators set the tone for the meaning of this work. “It’s personal, it’s political, it’s hard, it’s important, it’s part of everyone’s liberation. “ Head & Heart “Racism, among many things, is a form of trauma that operates generationally and in our everyday contexts. While the trauma is more acute and health-harming for POC, White people have lost a “connection” with their hearts and bodies as well; one that must be mended in the process of liberation. We know that healing trauma is not only a cognitive exercise, it is also a heart exercise that must be intentionally addressed to coax forward the beliefs that have hardened within it.” (racialrec.org) As the discussion continued, the slide presentation showed a satellite picture of the earth illuminated at night. The Northern hemisphere, dotted with specks of white lit up like a pointillism painting. It was like a resource contagion hovering over mother earth. The countries in the southern hemisphere weren’t as dotted in white, though many of the world’s resources come from these countries, especially South America. What does this represent? Equity and Equality Next was the discussion about “equity and equality”. What is the difference? They gave the common example of the gendered bathroom dilemma when at large events what happens during intermission or half-time? Who has to wait in line? They have similar facilities but the needs are different. “Equity is giving everyone what they need to be successful. Equality is treating everyone the same.” There have been images circulating on the web showing people looking over a fence at a baseball game. The problem with this image is what has been analyzed here. I prefer to look at the image below as a metaphor for equity & equality (RWJ Foundation): Next, the discussion turned to working definitions of “Racial Justice”. To summarize and add definition to the context of this discussion, these were the examples used in the presentation: Racial Justice ≠ Diversity (Diversity = Variety) Racial Justice ≠ Equality (Equality = Sameness) Racial Justice = Equity (Equity = Fairness, Justice) Disparities, Inequality, and Inequity DISPARITY = INEQUALITY and implies differences between individuals or population groups (UN-equal) INEQUITY refers to differences which are unnecessary and avoidable but, in addition, are also considered unfair and unjust As the discussion progressed I was struck by the repeated theme and sobering slides of public health data surrounding Boston health disparities. One most notable graph was the “Infant Mortality in Boston by Race/Ethnicity”. Slide after slide showed controlled studies between African Americans and White American households as it relates to infant mortality and education, household income, prenatal care, cigarette smoking and access to health care. To see the data show that Black women with higher education, access to health care, non-smoking, higher income and 1st-trimester prenatal care have higher infant mortality rates than less educated, poorer, no prenatal care, smoking white women is beyond distressing. Clearly, the health inequalities in the Boston area result from deeply entrenched structural racism.

The discussion looped into an analysis on racism. Racism, not race. What is Racism? “A system of advantage based on race.” This is a very simplistic definition of a complex word, complex topic. Heads nodded around the room, my assumption was a nod in solidarity and understanding. Levels of Racism Interpersonal: The ways in which racism is communicated between people or groups (can be signs, symbols, words, etc) Internalized: The way that racism is ingrained for individuals, different for white-identified and people of Color Institutional: The way that racism is embedded within institutions, the policies, and practices within institutions that perpetuate racism Structural: The relationship between institutions and how they work together over time to reproduce racism The facilitator then equated racism to groundwater. It is everywhere in America- “It’s in the groundwater” The perspective that structural racism is embedded into the fabric of American society lends me to feel overwhelmed and apprehensive about how to proceed. Race and racism isn’t a cocktail conversation in most circles, especially the non-POC crowd. So, it left me asking myself, “How can I, as a parent, a spouse, a counselor, a friend and a local community representative contribute to solving the groundwater problem?” The end of the workshop concluded with space for people to talk about their experiences that morning. The facilitator then asked how we would be taking care of ourselves for the rest of the day given the heaviness and emotion of this topic? Many in the room had to return back to work, many were hungry for lunch, several planned to go for a walk to digest everything discussed that morning and I concluded that I would write a blog entry about my experience today. Groundwater, how will it be treated?

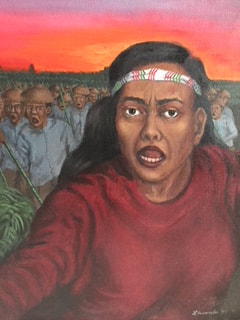

"The Gabriela" (1999) Acrylic. 20" x24" by Lewanda Lim

In 1999, Lewanda was commissioned to create a painting about the legendary Filipina warrior, Gabriela Silang, for a film documentary project entitled, "Tea and Justice". This painting is shown in the film's introduction and portrays Lewanda’s interpretation of this powerful woman warrior.

A summary of Silang’s life can be viewed below: Gabriela Silang: Anti-colonial fighter in the Philippines By Lacei Amodei April 27, 2007. Liberation Newspaper. Filipino women have a long struggle against oppression, foreign control and male domination. They fought for better jobs and the rights to vote and go to school. One of them led a regional revolt against Spanish colonizers. She was Gabriela Silang. —From the website of the organization GABRIELA “María Josefa Gabriela Cariño Silang, born March 19, 1731, and known as Gabriela Silang, is remembered as a fearless warrior and a great leader of the people of the Philippines. She was a military general in the resistance to Spanish colonialism and led the longest sustained revolt against the colonizers. Her brave legacy has persevered long past her death. The memory of Gabriela’s actions has continued to guide women and men in the struggle against imperialism. Gabriela was the daughter of an Ilokano peasant living under Spanish colonial rule in the Philippines. For hundreds of years, Spain dominated the Philippines through forced labor, excessive tax collection and payment of tributes. Imperial Spain’s three centuries of colonialism were not accepted passively by the Filipino people. At least 300 significant armed revolts against cruel Spanish repression were launched by the indigenous peoples of the Philippines. Gabriela first married a wealthy man when she was 20 years old. After three years, she left the marriage and later remarried a 27-year-old indigenous Ilocano resistance leader named Diego Silang. Gabriela was not only Silang’s partner; she was his equal and closest adviser. During the Seven Years’ War—a war between Spain, Britain, France and other colonial powers of the day—Diego Silang was imprisoned by the Spanish. Spain was allied with France and others against Britain during the war. Britain was attempting to diminish the Spanish empire. It invaded the Philippines. Diego Silang was imprisoned after he suggested to the Spanish authorities that they abolish the tribute, colonialist tax, and replace Spanish functionaries with native people. He volunteered to head Ilocano forces against the British. The newly appointed Catholic Bishop of Nueva Segovia rejected his call. Diego Silang’s imprisonment stirred an Ilocano revolt. After his release, he roused his people to action once again. His effort was cut short when he was assassinated by a traitor paid by the Catholic church. Following his death, Gabriela took on full leadership of the resistance. She moved into the Abra mountains to establish a new base, reassemble her troops and recruit from the local Tingguian community to fight the Spanish. Gabriela led the resistance group for over four months before being captured. She and around 100 resistance fighters were executed by the colonizers on Sept. 20, 1763.”

As a tribute to Gabriela Silang and a fundraiser for the "Telling Our Story" project, check out our Silang tank top.

|

AuthorMgaKwento is a storytelling collaboration exploring the intersection of art , ethnic identity development and experiences of the Filipino diaspora. Archives

October 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed